The last speakers – Yaaku language saved from extinction

The story goes that the Yaaku held a meeting in the 1930s and decided to relinquish their language and from that moment on speak only Maasai. At the time they were already in close contact to the Maasai, whose culture they perceived as superior. Whether this was really such a conscious decision is of course doubtful. What is certain, is that in a public meeting held a few years ago, they decided to return to their native language. Now language usage is usually not a thing that can be decided by political decree, so this decision will be hard to realize.

The Yaaku were curious to hear the opinion of linguists on the question whether there is sufficient knowledge available in the community to revive the language. So in the first week of 2005 the Yaaku committee invited us to the town of Doldol in Central Kenya. Our travelling group consisted of Maarten Mous, linguistic researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands, Hans Stoks, pastoral worker with the Maasai in Kenya, and Matthijs Blonk, who will record the whole experience on video.

|

Stephen Lerico is a language purist |

Purist

Already during the official welcoming ceremony, we are treated to a short conversation in Yaaku between an old man and an old woman. Remarkable, since according to several scientific publications, Yaaku is extinct. The old man is called Stephen Leriman Lerico. He turns out to be a vigorous proponent of the Yaaku language. He speaks it clearly, but slowly and tentatively. Because he is a purist, he has to search his mind for the right words. He tries hard not to use any Maasai words and corrects others if they do. The old woman, Yaponay, turns out to be the best speaker.

The next few days we work with these two people, recording words and sentences. Yaponay invariably turns up at these sessions with her three great-grandchildren. She carries the youngest on her back. The old woman takes care of the children because both the parents died. It is a heavy task for a woman alone, especially if you think that she must be about one hundred years old. Her age can be deduced from the name of her age group, Terito, going back to a Maasai system to name every generation which is circumcised within a time span of seven years.

| Yaponay is about a hundred years old, but still takes care of her great-grandchildren |

|

Shuffle

Two Yaaku speakers are not enough to get a complete picture of the language. According to the Yaaku committee in Doldol, there have to be more. With a guide we trek into the hills to look for Legunia, an old man belonging to the same age group as Yaponay. He is a small, frail man, shuffling along, but still keen. Stephen and he greet each other in Yaaku at length in his home. But as soon as he is aware of the microphone, he is reluctant to talk. A few days later we manage to persuade him to come to Doldol for a meeting of all the Yaaku speakers in the region. It is quite a feat for him to undertake the long walk to the village with his shuffle.

Unfortunately we cannot get him to make a real speech, or produce an account of more than a few sentences. Quite abruptly he has had enough and starts to leave. But his few words have shown him to be a fluent speaker, who does not have to think before he speaks. Apart from Legunia, Stephen and Yaponay, a younger brother of Yaponay is present, Jomo Lelendola. He knows a lot of words in Yaaku, but has a hard time producing a simple sentence, let alone a longer speech. Not surprising if you bear in mind that for the Yaaku elders, this is the first conversation in their own language since several decades. They are used to speaking Maasai, except for Yaponay, who speaks Yaaku with her great-grandchildren.

More speakers or semi-speakers of Yaaku are not to be found in the region around Doldol. There is an old woman who allegedly speaks the language, but she doesn’t respond well to our visit. She nags about money and refuses to cooperate. Hans Stoks has worked with two old elders a year ago, but they have passed away. Scattered around Kenya there are some aged clan members who spoke Yaaku in the distant past. The most hopeful clue we have is about a remote village called Nadung’oro, which is supposed to still house a few speakers. It lies at a day’s walk from Doldol, but luckily we can hitch a ride on a Landcruiser owned by the Catholic mission.

|

Legunia still speaks the language well, but refuses to speak into the microfone |

Elephant

Nadung’oro lies on a beautiful green plateau and consists of a string of boma’s, small fenced estates with one ore more houses and a stable. We arrive in the middle of a public meeting. The men are sitting in the shade of a tree. Nkapilil Supuko, our guide and president of the Yaaku committee, explains the purpose of our visit. His urgent plea for saving the language is received well. According to the men Roteti, an old woman, still speaks the language well.

We send theLandcruiser to her boma to pick her up. She arrives accompanied by her two daughters, and immediately bursts into Yaaku. She even manages to tell a whole story about an elephant. The story is translated by Kitime, who is one generation younger than Roteti. With some hope we work with Kitime at his boma later in the day. We find out that although he understands the language, he cannot speak it actively. It is interesting to note how he simplifies verb conjugation, but at the same time it is exemplary of the state the language is in.

After one week of research, we conclude that there are three speakers who still speak the language fluently: Yaponay, Roteti and perhaps Legunia. But all three of them are about a hundred years old, and they have a hard time thinking about their language and understanding what we want. Then there are people like Stephen Lerico, Jomo Lelendola and Kitime who understand the language and are able to speak it to a certain extent, but for whom the grammar is no longer intact. And finally there is the group of people who know a few Yaaku words, but who are unable to form a sentence.

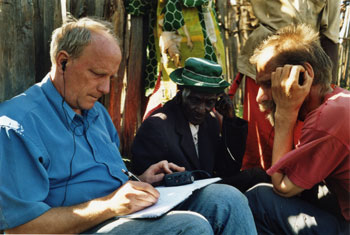

| Roteti and her daughters are interviewed by Hans Stoks and Maarten Mous |

|

Emancipation

According to the Maasai, the Yaaku are Dorobo. This is their name for all peoples who do not keep cattle, and who depend largely on what nature provides, a way of life which the Maasai hold in low esteem. They often have longstanding trade relations with these peoples, trading milk and meat for honey. But it is the Maasai who state the terms because of their military prowess and their feeling of superiority. A Dorobo will try to pass himself off as Maasai to rise in status. That’s how the Yaaku turned into Maasai. They keep cattle, they dress as Maasai, they bear Maasai names, and they speak their language. Deep in their hearts they are ashamed of being of Dorobo origin.

Presently there is a counter-movement. Now that the Yaaku identity has all but disappeared, the sense is growing that something valuable is about to be lost. As a Yaaku, one does not have to feel like a second rate citizen, as any Maasai of Dorobo origin will inevitably feel. The emancipation which is taking place among the Yaaku is mainly aimed at winning back their self-respect. The one thing which most clearly distinguishes the Yaaku from the Maasai is their language. It is easy to borrow outward characteristics like clothing, but one cannot put on another language in the morning.

The Yaaku movement wants to try to restore the Yaaku identity by reviving the language. A sense of identity is important for development. Only a clear identity will make their claim to Mukogodo forest bear weight. Only as a separate people distinct from the Maasai, a people who have maintained the forest for hundreds of years, can they claim it as their communal property. The issue is very much alive, since the Kenyan government is preparing a new constitution which might accommodate the land rights of the Yaaku.

|

Nkapilil Supuko is chairman of the Yaaku organization |

Tribal conflict

Both the Yaaku emancipation movement and the attention the Kenyan government has for ‘original’ peoples are a consequence of ten years of international attention for indigenous peoples, generated by the UN Decade of Indigenous Peoples, which ended last year (immediately followed by a second Decade). But there still remain many peoples who are not so fortunate in gaining attention. For instance, the Yaaku are not the only Dorobo in East Africa. In Kenya there are the Ogiek. But others include the Akiek and Aasax or l’Aramanik in Tanzania, and other small marginal peoples who try to live off the land, like the Dahalo in Kenya or the Ik in Uganda. The mere coincidence that a member of the people in question has had the chance to go to college and learn to operate through international channels, seems to be the only factor which determines whether a people get any attention.

Complicating the question of Yaaku land rights is the matter of another land conflict in the area. Last year was the termination date of a treaty signed in 1904 between the British colonial rule and Maasai leader Laibon Lenana. It leased a great area of Maasai land to white farmers for one hundred years. According to the treaty, the land would remain the property of the Maasai. The area borders on and overlaps with the area where the Yaaku currently live, and so parts of Yaaku land are also claimed by Maasai. This claim of two peoples to the same land could easily lead to a tribal conflict in this already relatively overpopulated area.

| Maarten Mous and Hans Stoks working with Kitime at his boma |

|

Strategy for language renewal

There are several peoples in East Africa whose language is or has been in the same situation as the Yaaku language. The Mbugu in the Usambara mountains in Tanzania are from the same original area as the Yaaku, according to their oral tradition. They too are supposed to have once spoken a Cushitic language close to Yaaku (other Cushitic languages are, for example, Oromo and Afar in Ethiopia). There are in fact some words which could indicate a connection to Yaaku. The Mbugu have turned to speaking Pare, a Bantu language, all but losing their native language in the proces. But nowadays the language is thriving, be it in a very peculiar form.

The Mbugu now speak two languages: one which closely resembles Pare, and one which shares its grammar with Pare, but uses a different vocabulary. They constructed this hybrid language when they realized that they had lost their own language and only spoke Pare. They mixed as many words as possible of their old language through the Pare, adding words from other languages like Maasai or Iraqw, as long as they didn’t resemble Pare. This hybrid language provided them with an identity.

This method might be an option for the Yaaku aswell. If they are determined to revive their language, they could keep the Maasai grammar which they learned as a child, and replace as many words as possible with original Yaaku words. That’s why it is important that the Yaaku get a dictionary of their own language. We could provide it for them, together with cassettes containing spoken words and stories, to practise pronunciation. Schools would be willing to take up Yaaku in their curriculum, if they are provided with the proper material. Of course it is essential that the few remaining speakers keep on speaking the language among themselves and with others of the community. It has been suggested to settle the remaining speakers in a single ‘language-boma’, to create a core group of Yaaku speakers.

Maarten Mous is professor of African Linguistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

Hans Stoks is pastoral worker in Kenya and an expert on the Maasai.

Matthijs Blonk works for NCIV and is currently working on a film about the Yaaku language.

English translation by David van Eijndhoven of the main article of the may/june 2005 issue of Indigo,

magazine on indigenous peoples.

© Indigo magazine, Amsterdam, Netherlands